Marcel Proust, Ovid, and the Dangerous Art of Failed Love

Why is there no successful Eros in In Search of Lost Time?

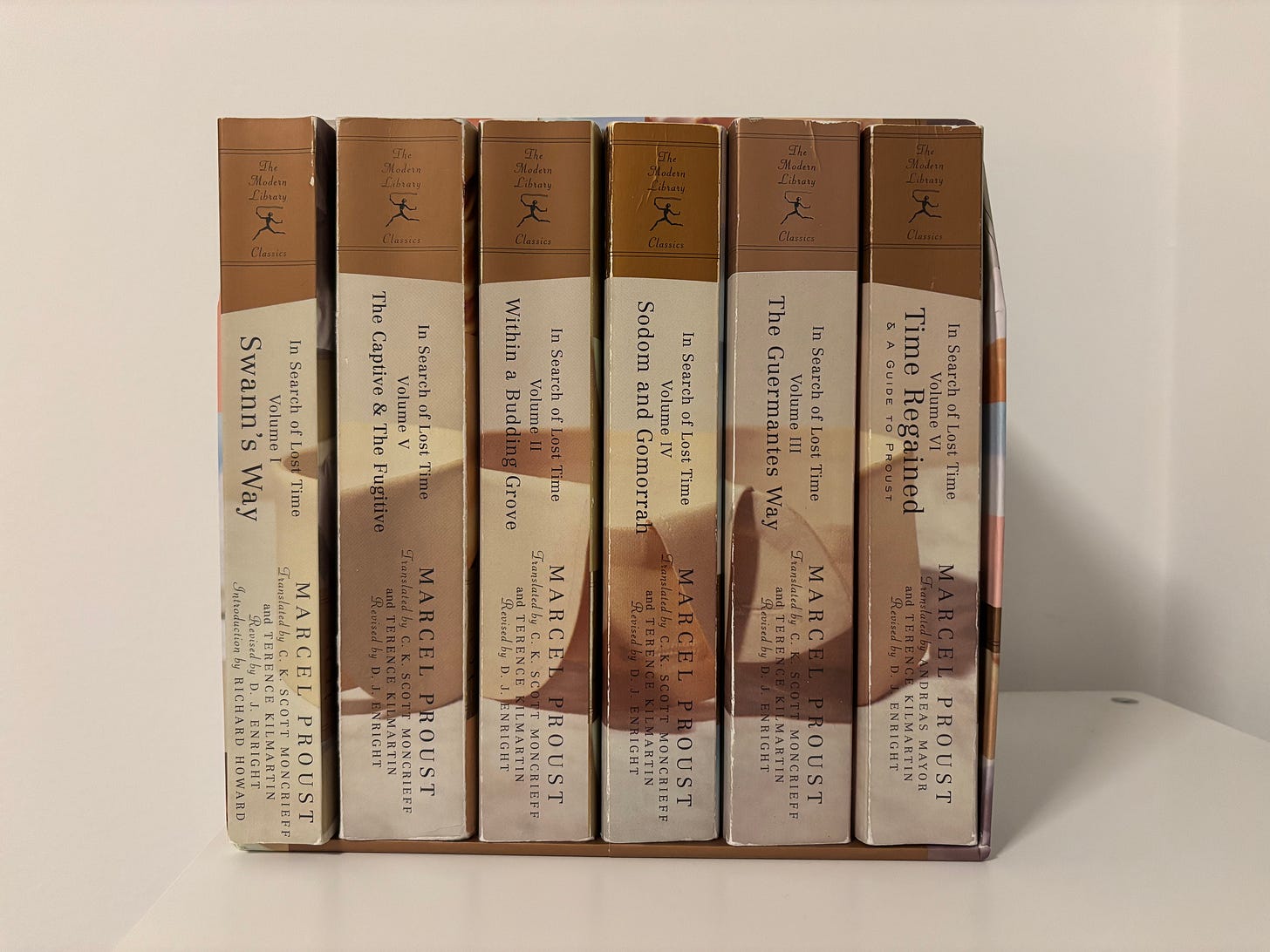

I have lately finished reading Proust’s 4,000+ page epic of French literature, In Search of Lost Time. It is difficult to begin talking about this novel because of the wealth of things that one could say. So I have simply decided to focus on one small error of nihilism that I see in the text: the notable absence of successful romantic love in this otherwise totalizing portrait of human experience.

I want to talk about two seemingly distant literary giants: Marcel Proust (early 20th-century French novelist) and Ovid (ancient Roman poet), and how both posit love as a transformative force—but a dark transformation, a process that dehumanizes the beloved rather than uniting with them.

Both Proust and Ovid show us what happens when love fails, grows toxic, and the lover, left with nothing tangible, transforms the beloved into an object of aesthetic or symbolic value. In Proust’s case, the “object” is an artistic creation; in Ovid’s, it’s an actual physical transformation.

Proust’s masterpiece is divided into seven volumes, each chronicling the social and internal life of a narrator known as “Marcel,” and venturing, through free indirect style, into the psychological lives of Marcel’s contemporaries, especially, as it relates to this essay, Swann.

It is troubling to note that there are zero stories of successful romantic love in the novel, and this in my opinion comes from Proust’s contentions that we cannot know another person, and that ultimately art is the only consolation. By the final volume, the narrator has abandoned the idea of finding romantic love. Instead, he retreats into solitude to write his novel—the very one we’re reading. In Proust’s world, art becomes the triumphant alternative when romantic fulfillment proves impossible.

I think his reflection, after he parts with finally with Gilberte, his first youthful love (and the daughter of Swann), is telling:

“When I succumbed to the attraction of a new face, when it was with the help of some other girl that I hoped to discover the Gothic cathedrals, the palaces and gardens of Italy, I said to myself sadly that this love of ours, in so far as it is a love for one particular creature, is not perhaps a very real thing, since, though associations of pleasant or painful musings can attach it for a time to a woman to the extent of making us believe that is has been inspired by her in a logicallyx necessary way, if on the other hand we detach ourselves deliberately or unconsciously from those association, this love, as though it were in fact spontaneous and sprang from ourselves alone, will revive in order to bestow itself on another woman,” (p. 299, Place-Names, The Place.)

Note that Marcel is thinking of love as a feeling, not as an act and an ongoing process of creation. Meanwhile, he also immediately associates love with the act of contemplating aesthetic beauty, disclosing a propensity to reduce love to ‘a beautiful thing,’ which is not, meanwhile, true beauty—for though a Gothic cathedral or an Italian garden may indeed be beautiful to look upon, it is not Beauty itself, namely the form of Beauty, which is bound up with the True and the Good, of which nexus love is an expression.

Of the love stories in the book, I submit that none are successes, insofar as there is growth and unity between the lovers. The novel is peppered with extramarital affairs, hidden desires, and marriages of convenience. Proust rarely offers a contrapuntal healthy, enduring relationship—everyone is trapped in an endless cycle of suspicion and heartbreak. My friend M has challenged me on this, suggesting that there is one love story that subverts this dismal conclusion. Though I don’t think enough information is presented in the text to fully substantiate this, I will discuss this love story at the end. Meanwhile, the list of failed loves is overwhelming: Marcel and Gilberte, Marcel and Albertine, Swann and Odette, Charlus and Morel, Morel and Jupien’s niece, Oriane and the Duc de Guermantes, and more. For the pride of place that romantic interaction is given in the work, there is not much love or hope produced. Let’s look at Swann first.

Swann and Odette

Swann is a cultured socialite celebrated in aristocratic salons. Odette is not well-liked by those same circles. Despite their mismatch, Swann falls in love, despite recognizing that she ‘isn’t even his type’ (p. 276). But why? It’s because Swann sees love as aesthetic beauty, obsession, and feeling, rather than a union of souls that will ennoble them both. Indeed, Swann finds Odette tasteless, tacky. But he falls in love with the idea of falling in love with her:

“But at the time of life, tinged already with disenchantment, which Swann was approaching, when a man an content himself with being in love for the pleasure of loving without expecting too much in return, this mutual sympathy, if it is no longer as in early youth the goal towards which love inevitably tends, is nevertheless bound to it by so strong an association of ideas that it may well become the cause of love if it manifests itself first. In his younger days a man dreams of possessing the heart of the woman whom he loves; later, the feeling that he possesses a woman's heart may be enough to make him fall in love with her,” (p. 277, Swann in Love).

It is love as obsession, possession, feeling, rather than mutual fulfillment. Swann, for example, becomes insanely jealous of Odette’s relationship with Forcheville, an aristocrat. He literally goes out and searches for Odette around Paris when he doesn't know where she is, and suspects she’s with Forcheville. It is in an effort to possess her, not to love and ennoble her, that Swann makes love to and eventually marries Odette. Indeed, even at the end of his love story, when they are wed, he returns to his initial lament: “To think that I’ve wasted years of my life, that I’ve longed to die, that I’ve experienced my greatest love, for a woman who didn’t appeal to me, who wasn’t even my type!” (p. 543, Swann in Love).

Meanwhile, the aestheticization of the lover is ever present, when Swann sees Odette as a fresco by Botticelli:

“She struck Swann by her resemblance to the figure of Zipporah, Jethro’s daughter, which is to be seen in one of the Sistine frescoes. He had always found a peculiar fascination in tracing in the paintings of the old masters… the individual features of the men and women whom he knew.” (315)

Marcel and Albertine

Marcel, the narrator, a vague but inaccurate analog for Proust himself, has two great and several minor love interests over the seven volumes, none of which materialize in any productive way. The first major love story is with Gilberte, Swann’s daughter, the reflection on which you’ve just read above.

But the novel’s most haunting romance is between Marcel and Albertine. Marcel, plagued by jealousy, manipulates Albertine, essentially holding her captive in his Paris apartment. He suspects she might be in love with other women, and his inability to know her—truly and fully—becomes an all-consuming torment. From her first moments with him in his apartment, Marcel acknowledges that his love is corrupt, and based exclusively on jealous possession:

“Without feeling to the slightest degree in love with Albertine, without including in the list of my pleasure the moments that we spent together, I had nevertheless remained preoccupied with the way in which she disposed of her time,” (p. 18, The Captive).

(It is interesting to note that Marcel is especially concerned that she is having lesbian affairs behind his back, or, with even more pernicious jealousy, that she has lied to him about having had lesbian affairs in the past. His reason for this is that he feels he cannot provide the same type of romance for Albertine that she receives from women; whereas he could beat another man at his game, since he is a man, he cannot beat a woman at hers.) Marcel wants to know what she is doing, but not how she is feeling, or who she is. This may spring from Marcel’s contention that another person cannot be known. This is where Marcel misses the true nature of love, which is beauty integrated with truth (and morality). This can be seen, for example, in the evolution of his opinion of the Guermantes family over the course of the third volume: he adores and worships their name and their history, but as he discovers that Oriane, the Duc, Charlus, St. Loup and the rest are simply normal, average people with expensive things, he becomes disillusioned—instead of progressing from affection to love, he progresses from infatuation to disillusionment, because he does not want to know the truth, he wants to preserve and sustain a fantasy.

The impossibility to knowing someone can be seen also in his inveterate distrust of Albertine, whom he keeps as his prisoner. Moreover in statements such as, “Man is the creature who cannot escape from himself, who knows other people only in himself, and when he asserts the contrary, he is lying,” (The Fugitive, 607). But at the same time, it seems like Marcel has never endeavored to know the real Albertine, nor Swann to know the real Odette. Everyone, is aetheticizing their lover, keeps them in the realm of the idea, and never reifies them; to love is to love a human—granted, with a soul, but embodied, nonetheless… and yet we read:

“It is perhaps one of the causes of our perpetual disappointments in love, this perpetual displacement whereby, in response to our expectation of the ideal person whom we love, each meeting provides us with a person in flesh and blood who yet contains so little trace of our dream,” (The Fugitive, 612).

Ultimately, as could be foretold of a woman kept locked away, Albertine leaves Marcel. He tries to get her to come back to him, thinking that he loves her after all, but she is tragically and surprisingly killed in a fall from a horse. Thus ends the protagonist’s last significant attempt at romantic love, whereafter he begins his retreat from social life, into the seclusion from which he will produce his novels, and effect Albertine’s transformation into a work of art. Albertine’s transformation comes not, however, by an offhand comparison to Botticelli: rather, she is transformed, in a metafictional sublimation, into the very novel that the reader is now holding in his hands.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the Tragedy of Transformation

If Proust writes about emotional turmoil in salons and Paris apartments, Ovid sets his stories among gods and nymphs who roam forests and rivers. Yet the emotional core is strikingly similar. Indeed, the love of possession that Phoebus and Pan feel respectively for Daphne and Syrinx transforms these women into aesthetic objects, too.

“Phoebus’s first love was Daphne, daughter of Peneus, and not through chance but because of Cupid’s fierce anger. Recently the Delian god, exulting at his victory over the serpent, had seen him bending his tightly strung bow and said ‘Impudent boy, what are you doing with a man’s weapons?’” (I:~438-472)

Phoebus makes the mistake of insulting Cupid and his little bow, and for revenge, Cupid strikes Phoebus with an arrow to make him fall in love with Daphne, and Daphne with an arrow to make her repulsed by Phoebus.

“[Cupid] took two arrows with opposite effects from his full quiver: one kindles love, the other dispels it. The one that kindles is golden with a sharp glistening point, the one that dispels is blunt with lead beneath its shaft. With the second he transfixed Peneus’s daughter, but with the first he wounded Apollo piercing him to the marrow of his bones,” (Ibid.).

Daphne flees from Phoebus, and never yields to him, no matter what he says or does. When he finally captures her, to avoid his assault, Daphne begs her father Peneus to use his “divine powers change me” and “destroy this beauty that pleases [Phoebus] too well!” (I:525-552).

Her father accedes to her request, and transforms her into a laurel tree. Phoebus then takes laurel branches from her transformed body and fashions wreaths around his head and quiver—even now, branches from Daphne’s mutilated body still symbolize imperium, and poetry: a ‘poet laureate’ wreaths himself in Phoebus’s shame, in Phoebus’s aggressive reduction of Daphne into an aesthetic object.

So too with Pan, who, trying to capture the nymph Syrinx, causes her to request a similar transformation—this time into reeds. Syrinx, having been transformed into reeds, is then cut from the river by Pan, who fashions her new body into a woodland pipe, a flute.

And how different is Marcel’s transformation of Albertine into a novel?

One of the most intriguing parallels is the idea that love, when it fails to become a mutual exchange, can turn possessive. Then, to cope with that failure, the lover “immortalizes” the beloved in art—be it a tree, a flute, or a novel.

Both authors underscore the human impulse to create when we cannot fully possess. Yet the moral or emotional cost is huge: the living, autonomous individual is effectively lost in favor of an artistic symbol.

Proust ultimately suggests an almost total impossibility of genuine connection. After finishing his epic novel, it’s tempting to walk away thinking that maybe he’s right—that human intimacy can never truly succeed, and art is the only solace for our inevitable heartbreak.

But I’m not so convinced.

So what is the right connection between love and art?

Love and art are near to eachother as concepts. Both are celebrations of truth, beauty, and goodness, or at least they can be. There is no need for one to interfere with the other in any significant way.

However, if your love does not celebrate truth, beauty, and ethics, neither will your art. In my own experience, it is even possible to have a false celebration of these three categories in love, and to have this simulacrum carry over into art. That is, you may be talking regularly with your lover about your art, but rather than focusing on the honesty and beauty therein, you will be talking about the mechanical craft instead. Your love, meanwhile, is taking the same shape, evolving in the same way. You are loving as if it were a mechanical craft, instead of an art form.

Love and art will only in the proper environment both be transformative powers. The direction of Proust and Ovid’s transformations are unilateral, but a bilateral transformative power, a symbiosis of love and art is entirely possible. You learn something about your life during your relationship, and you commit it to the page or the canvas. You learn something about yourself or your partner through reading or looking at a painting, and you bring that insight back into your conversation with your lover, using the insight to deepen the commitment to honesty.

Love does have a symbiotic and bilateral transformative power. So does art. Both partners can grow through it, becoming more of what they are. Or they can become hollow and aestheticized objects. It depends on the honesty, ethics, and aesthetics that you bring to the relationship, and to the craft.

Both of these practices—loving and creating rightly—are difficult to actualize, but the reward for doing so is greater a hundredfold than the cost thereof: you may, unlike Marcel, live a beautiful life.

Postscript: Jupien and Charlus

The Baron de Charlus is one of the wealthiest and most popular men in Paris. He is a member of the Guermantes family. Jupien is a tailor, whose shop is located in the Hôtel de Guermantes. He and Charlus meet and surprisingly make love in Sodom and Gomorrah. Their relationship lasts for the remainder of the novel. My friend M argues with me that this is the one instance of successful Eros in the novel.

M: I also have a Q for you. I agree that the novel is very interested in failed love, and almost all the romantic relationships in the novel fail. But I think there is one relationship—a big one-that does not fail! It is, to me, an instance of highly successful romantic love! I'm interested if you can think of the one I'm thinking of, hiding in plain sight. Because I think it is part of the novel's implicit "argument." Maybe it's not some people's image of love, but IDK, interested in your thoughts.

Torben [five hours later]: I give up.

M: What do you think of Jupien and Charlus? Obviously the relationship involved power and class dynamics and is strategic.

Torben: I thought of that for a bit actually.

M: But they also get along super well and their relationship lasts decades.

Torben: I see what you're getting at. Yeah.

M: And I can't rly remember it but I remember feeling earnest romance vibes.

Torben: "What a big bum you have!”—one of my fav lines in the book.

M: That scene is mind-blowing. The Shakespearean 'spying' that transpires. How it happens like 1000 pages in. So u experience it as just as shocking a revelation as the narrator does—ab how the world works.

Torben: Yeah deadass.

M: He even describes their bond as sort of chemically unique and unlikely, the perfect insect for the perfect flower. How each is the other's 'kink.' Or like how Charlus is lucky to find this guy who is into older men. Or later, Jupien procuring the BDSM scenes for Charlus.

Torben: Yeah that procuring is what kind of threw me off the scent, when you asked who I thought you meant. Like it seemed like he was instrumental to Charlus at the end. Like a means not an end. But maybe Charlus just getting old.

M: Yeah I think it's not entirely clear. I remember experiencing it as like a kind of gesture of caring and selflessness from Jupien. He provided the scenario and participants for his lover. And like in order for Jupien and Charlus's relationship to remain above-board they have to persist in inhabiting their class roles of servant/ruler. Which sometimes they perform but sometimes become the natural, normalized positions they inhabit. So Jupien doing these things is his 'job' because that's the 'cover' they take on to hide their gay relationship. And sometimes his 'job' duties intermingle with being a lover. There's a spectrum. IDK just one reading. Obviously Jupien 'uses' Charlus for shelter, access to power, resources, lifestyle benefits. And Charlus 'uses' Jupien's body and manual labor. But whether or not they deeply emotionally connect on a romantic level is sort of obscured from us, and if their relationship in aggregate is more fulfilled than say Albertine-narrator is not clear. But I think there are grounds for arguing it's the most successful romantic relationship in the book.

If you’d like to purchase Common Measure Vol. I, you can do so at

https://commonmeasure.press/